In Memoriam Owen de Long

1939 - 2013

In Memoriam Owen de Long

1939 - 2013

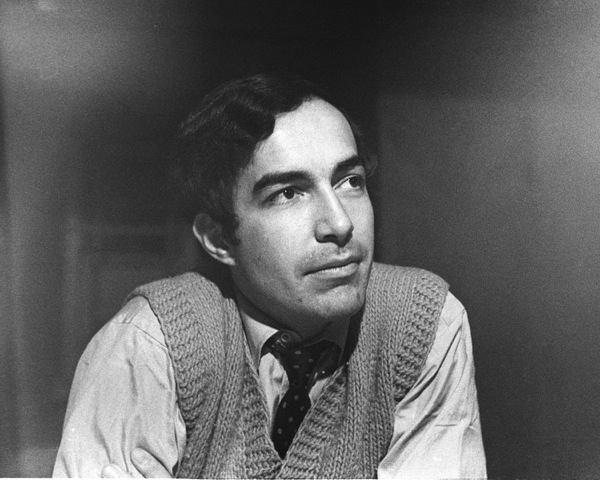

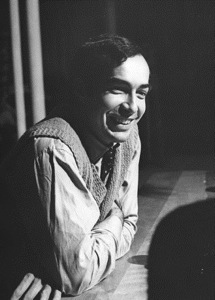

Owen de Long was born on March 31, 1939 to Ethel and Alfred de Long. His father was trained as an opera singer and his mother as a concert pianist. Both had brief careers in performance before the Depression hit. His father then had the good luck to land a job at Western Maryland College in Westminster, Maryland, teaching voice and choir; his mother taught local children the piano. It was not the career either of them had expected, but his father soon became a much loved figure in the college, with many students to whom he imparted his love of music.

When the couple’s second child, Suzanne, was in second grade, Owen’s mother was hospitalized for a “nervous breakdown,” which we would now call severe depression. Owen was sent to McDonogh military academy on a full scholarship. He tried to run away from McDonogh several times, but was always caught and brought back. He decided, finally, that the only way out was out the top, and began to study with the drive that later characterized everything he did.

His record at McDonogh took Owen to Harvard on a full scholarship. As a freshman at Harvard in 1957, he was given a room in Thayer Hall, in Harvard Yard, a building that consisted entirely of scholarship students. At that time, students paid differential fees for their rooms depending on the quality of the room, and the Thayer rooms cost less than the others because they were relatively small, with two beds in a room and no separate common room. Owen did not consider this environment a healthy one. He pointed out later that of the 30 or so freshmen in his entry at Thayer, only he and one other made it through Harvard without taking a leave of absence, dropping out, or committing suicide. The scholarship students were all new to an environment like Harvard, were insecure about their status and their capacities to do the work, and had only one another to whom to turn.

Owen had gone out to Wellesley for the college’s first freshman “mixer” of the year, and had danced there with Jane Mansbridge, at Munger House. He asked her out and she began to join him for events at Harvard. Public transportation to Wellesley was time-consuming and difficult, so Owen borrowed friends’ cars until sophomore year, when he and a friend were able to buy together an old car that would make the trip. Except for the first semester of sophomore year, Jane and Owen went together all through college.

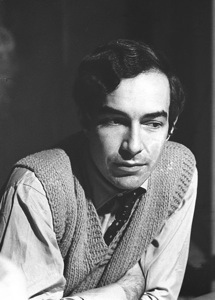

In his sophomore year, Owen moved to Adams House, where he became friends with a group that included John Nathan and Bob Leiken. At Adams House Bob remembers first viewing Owen “from afar as a dark, dashing, cool, seemingly supremely confident stranger,” but as he got to know him realized that both he and Owen had “derived from mutually, if differently, Dickensian childhoods; which would lead, in our so-called adulthood, to mutual if very different rebellions and rectifications.” Alec Watson remembers Owen from Adams House as “smart, energetic, and very knowledgeable about music, especially lieder -- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was high in Owen’s pantheon.” Daniel Seltzer, the senior tutor at Adams House in those days, organized several plays in which Owen and his friends acted as a kind of “house company,” with Owen playing minor roles.

Although in his freshman year Owen had been on the crew, after he got to Adams house he turned his energy not only to acting in the house but also to the Harvard University choir. He remained in the choir through his senior year, singing in the chorus of an extraordinary performance of Mahler’s Requiem. Jane remembers his playing her Mahler lieder in his room and their crying together at the beauty of the songs.

In the summer of Owen’s junior year, Jane’s parents were planning a trip to Yugoslavia, and Owen applied to an exchange-student program in which he was given a job at the Belgrade office of the export-import company Centroprom, while Jane’s father produced a job for a Yugoslav student in the New York office of Cambridge University Press. Jane had written to her parents that she and Owen had become engaged in order to facilitate family interactions over the summer. In Yugoslavia Owen became friends with the head of the Workers Council of Centroprom, a tall, blond, and gregarious executive, proud of his peasant upbringing and the Communist Party that had brought prosperity to him and his country, who later became Yugoslavia’s Ambassador to Egypt. Owen also became good friends with a man of bourgeois parentage, who spoke good English and had been educated for a year or more in London, knew that he had no chance of rising above accountant in the current order, and was disaffected from the regime. He and Owen spent a lot of time talking about girls. These two reflected the breadth of Owen’s capacity for friendship.

Owen majored in philosophy at Harvard, and in his junior year took a tutorial with Robert (Bob) Paul Wolff. Bob remembers Owen as “a bright, handsome young man” who held his own in a “remarkable little tutorial group” of five philosophy majors that included Tom Cathcart (author with Dan Klein of Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar, an exposition of the main fields of philosophy through jokes, and The Trolley Problem) and David Souter (who later became a justice of the US Supreme Court). Influenced by Wolff’s Kantian scholarship, Owen wrote his senior thesis on Kant.

Owen became involved in politics through Tocsin, the Harvard disarmament group. Jane remembers a long phone call they had in their junior year, 1960, when he gradually persuaded her that this was not an absurd cause but instead an urgently important one in which the public at large was not aware of critical facts. He had been brought into the group, and later into the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Politics, by his good friend Benjamin Barber, whom he met in the summer of 1959 when he worked as a waiter in Ben’s father’s resort in the Berkshires, the Music Inn.

Owen’s new political interests led him to apply to the Ph.D. program in the Department of Government at Harvard, where he was accepted for the fall of 1961. He also applied for and received the prestigious Danforth fellowship for four years, which had been until that time generally reserved for scholars with a religious commitment. Owen, who wrote an application based on Kantian morality, became one of the first scholars awarded the fellowship on the basis of a broad conception of moral values.

Jane and Owen were married on June 17, 1961, right after they graduated. John Nathan, Bob Leiken, and Alec Watson, Owen’s friends, were ushers and Suzanne de Long, Owen’s sister, was Jane’s bridesmaid.

Suzanne de Long

Jane and Owen being driven from church

Owen in receiving line

Jane and Owen cutting the cake

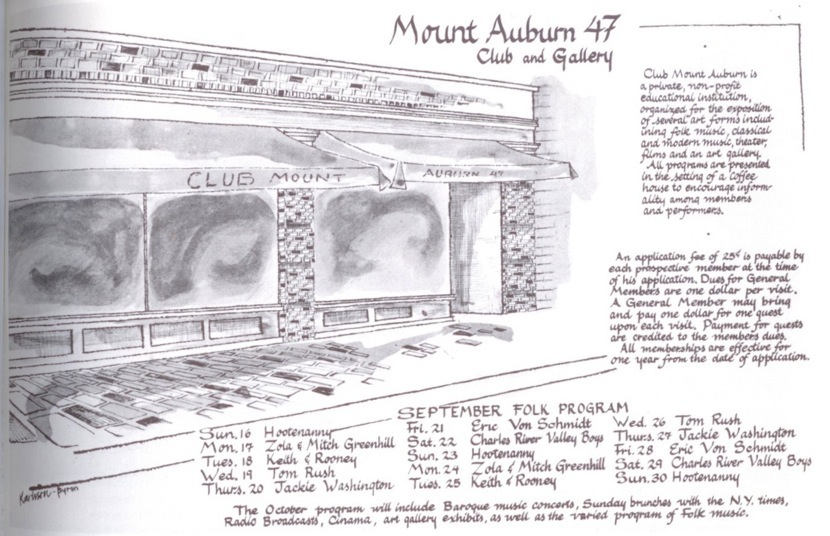

Club 47 calendar, September 1962, with sketch of the club on Mt. Auburn St.

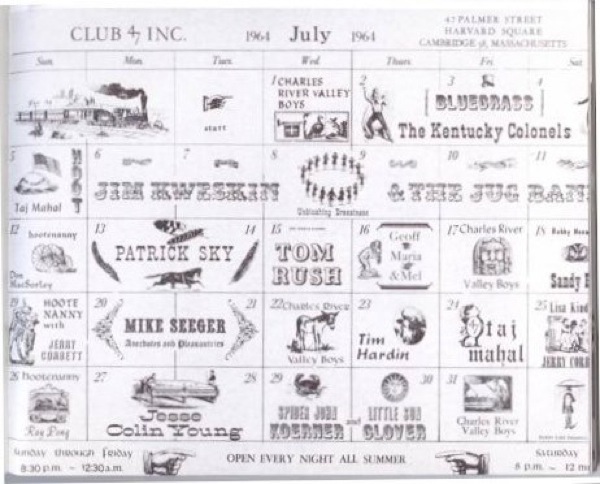

Club 47 calendar July 1964, designed by Byron Lord Linardos, after the club had moved to Palmer St.

When Owen and Jane returned to Cambridge after a summer in New York, Owen made a typical coup by finding a tiny inexpensive studio apartment directly across from Widener library in the heart of the Square. The apartment had a double bed that served as a couch, two canvas butterfly chairs, a Festinger reproduction on the wall, a floor-to-ceiling bookcase with a two-foot wide desk, which Owen built in an alcove, and a kitchenette. The two ate inexpensively, with tuna casseroles using Campbell’s mushroom soup and potato chips a frequent dish. One day when they were having supper on a concoction of Minute Rice and canned tomatoes with slices of hot dog in it, Jim Rooney dropped by and asked, aghast, “Do you always eat like this?”

Both Owen and Jane were working hard at graduate school, sometimes finishing the evening of study by going down to Brigham’s in the Square for a chocolate ice cream soda just before it closed at midnight. But the Club 47, which had opened in 1958, was just coming into its own and offered memberships that gave members free access to the club. Owen decided they should each get a membership, and from then on the club, only a few blocks away on Mt. Auburn Street, became their after-work hangout. Anyone with a membership could go in late, stand in the back, and take in the last set of the Charles River Valley Boys, Bill Keith and Jim Rooney, and others – some of whom, like Rooney, Bob Siggins, and Ethan Signer, were also graduate students at Harvard or MIT. It was a heady time.

Loving the music and the scene, Owen became friends with many of the musicians at the 47, began to hang out with Geoff Muldaur, with whom he had, in Geoff’s words, “many great times,” and worked with Betsy Siggins planning concerts in Sanders Theater.

Betsy remembers “a gentle memory of a gentle man. I met Owen and Jane in the heydays of the 60s' when everything seemed possible and our lives were wrapped in the wonderness of the folk music revival. We were part of the growing openness of most things 60's and open to much of it. Owen had a softness that was compelling to many women, and I was one. I didn't know him well; we went in different directions; but I always remember those heady times as seminal in who I became. My thanks to Owen for being there.”

Maria remembers Owen and Jane coming over regularly to the tiny house she and Geoff had on Rockwell St. where she would whip up a batch of her chicken cacciatore, and after supper she and Jane would hang out, discussing all their newly learned domestic and cooking skills and discoveries, while Owen and Geoff went over for “last call” at the Oxford Grill.

Maria continues:

But the thing that I remember the most about Owen de Long, that enshrines him forever in my heart, is that late in the summer of 1964, when I was about 3 ½ months pregnant with my daughter Jenni, Owen saved my life and hers! Geoff and I and the whole Kweskin Jug Band, plus Owen and Jane, had just arrived on Martha's Vineyard, where the Jug Band was about to embark on a two-week stint at the Mooncusser, a folk club there. After eating a large and delicious lunch of lobster rolls, fried clams and quahog chowder at Gay Head, we all headed over to a private beach Geoff knew about. Geoff and his family had always summered on the Vineyard, and, being excited to be back at his favorite stomping grounds, as soon as he saw the ocean he couldn't wait to jump in! He picked me up and carried me into the water, despite my protests that I had just eaten a large lunch and wanted to chill a while! Hearing none of it, and accusing me jokingly of being “Chicken of the Sea”, he continued to bring me further and further past the breaking waves, till it was way too deep for us to stand, all the while both of us laughing and goofing around ~

But soon Geoff realized that we were in a riptide, which was making it almost impossible to swim back to shore, especially as I couldn't swim very well at all, and had a sweatshirt on that was now really weighed down with water! Geoff saw Owen about 50 yards to our left, swimming straight out past us, and started yelling for him to come help us, but at first Owen, thinking we were just shouting out a greeting, turned around, grinned, waved at us, and continued swimming further and further out into the ocean! Putting our two voices together and shouting for all we were worth that we were in real trouble finally got his attention and he stopped swimming straight out into the ocean, turned, and started heading towards us. I heard Geoff say “Hurry up, Owen! Help me! Maria’s gonna drown,” which was the first real notion I had just of just how much in danger I really was! When Owen was finally about 10 feet away, Geoff shoved me towards him, turned, and headed in for shore, confident that I was now in the hands of an able-bodied swimmer like Owen. Thank God Owen was such a strong and athletic swimmer! Steadfast, he patiently, slowly, but surely, got me closer and closer to the shore, pushing me shoreward when the waves would roll in, and holding me up when the riptide tried to pull us further out . After what seemed like an eternity, we finally made it into shallow water where the waves were just breaking, and too exhausted to even move my arm for 20 minutes, I just lay in the surf thanking God and dear, dear Owen for saving my life and the life of my unborn child! That night, after we had all recovered from the ordeal, we took Owen (& Jane!) out for a sumptuous lobster dinner -- something way above the level of our meager folk musicians’ budget, but certainly a well-deserved treat for our hero!

Owen was to play a major role in another pivotal moment of my life, when, six or so months later, he and Jane ended up being the ones entrusted to drive me to the hospital to give birth to Jenni, as Geoff was down in Philly, doing a gig with Mimi & Dick Fariña, when the “Blessed Event” decided to commence! I will never forget sitting in their living room listening to their brand-new Howling Wolf LP, and having a contraction every time Wolf sang "if you hear me howlin', howlin' for my darlin'" and moaned emphatically, ”Whooo Whoo Whooo Eeee”…. the perfect soundtrack for the occasion!

Owen was a tall, dark, handsome and gracious man -- my favorite kind! I owe him my life, and my daughter's life, and I am very saddened to hear of his passing.

Maria also remembers:

What I remember most vividly about Owen is his contagious enthusiasm for the music we were hearing in those enchanted Club 47 days. In his inimitable fashion, Owen did not just stop at his personal delight with the music but wanted to know all about its antecedents, including the influential elders who were still playing, and to teach others about it. He avidly tuned in to all the talk about the music’s roots that the musicians around him in Cambridge were exploring and could speak in detail about a wide range of music and musicians, past and present. One couldn’t help but be affected by his ardor and want to know and hear more. Owen was a listener and a scholar accustomed to research and his passion for finding out as much as he could about the music seemed boundless.

One day in the South End of Boston, Owen introduced me to a small cramped old record store wall-papered with yellowing photos of musicians, where for around fifteen dollars I bought two of my life-long treasures: a 78 of “Mood Indigo” recorded on the Brunswick label in 1930 and a sepia-toned photo of a very young Duke Ellington with the inked inscription “To Miss Dorothy Edwards, May you never be “Mood Indigo.” I fervently wish that Owen had been spared the dark times too.

In the summer of 1964, Owen was helping to manage the Mooncusser Coffeehouse in Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard where the roster of performers was astonishing in retrospect, including Doc Watson, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, John Hammond, Mississippi John Hurt, Tom Rush, and so many talented others. [To interject in Lynn’s narrative here, Jim Kweskin remembers that it was because Owen was running the place that the Jug Band played there for a whole week in the early summer and then played again for another whole week in the late summer. “I believe,” he says, “that it was Owen who made that happen.”] Characteristically, Owen devoted abundant warmth and focused energy to this enterprise. He was great at it. Owen was never one to do things half way. He was in his element surrounded by a community and bathed in the atmosphere of the music he loved so much.

Since those admittedly intense 1960’s, I have never been without the sustenance of the love of music and curiosity about its roots and its people that Owen nourished. I am forever indebted to him and the musicians I met through him for such enrichment. Whatever métiers he was defined by in the future, here is one to add, even if it is not the standard definition: he was without doubt a great Music Teacher.

Lynn Englund Sweezy writes:

Ben Barber, Owen’s friend from undergraduate years, remembers this time as “part of a tumultuous age in which neither love nor politics promised much stability, but in which we had to feel and think our way through in ways that made it tough for couples to remain couples for very long.” He particularly remembers hearing Bob Dylan sing at the Club 47 at one of his first performances. Ben said to Owen disdainfully, "What's that? He hasn't even got a voice!" Owen, he remembers, said back “with total conviction, ‘Dylan is special: a unique talent. You’ll see -- he's going to be a major force.’ Not those exact words perhaps, but a ringing endorsement of a talent it took me years to recognize but that Owen appreciated from the very first moment. Owen didn't always see things clearly, but when he did see, he saw to the very core of their truth.”

Eric Weissberg remembers coming up from New York, hanging out with Owen, and always having “a fine happy time in his company,” from taking in the very first of the Road Runner shorts, where “it was so hilarious that nobody in there could catch their breath,” to tooling out to the International House of Pancakes on Soldiers Field Road for a multi-topping Belgian waffle, to talking intently about their favorite music.

Owen had decided that the apartment across from Widener was too small for parties, so as soon as they could afford it he turned up another great find of an apartment, above the “Bick” (the Hayes-Bickford cafeteria) on the corner of Dunster and Mass Ave, also right in the heart of Harvard Square, which had a real living room, bedroom, and kitchen. Owen also bought, on the installment plan, a brand new Chevy Corvair in racing green with black seats, which he ordered specially from the factory through a deal he had made with one of the Boston-suburban auto dealers. (Eric Weissberg says that that model is now “an iconic piece of motoring history.” Owen had an eye for the cutting edge.) Jane remembers how in that car the two of them drove to Mexico via New Orleans, pulling in to Preservation Hall just as a standard evening concert of New Orleans jazz was beginning, meeting at intermission Allan and Sandra Jaffe, who in 1961 had begun the venue for the evening concerts, sleeping that night in the Jaffes’ living-room, and spending the next day with them at the funeral of one of the jazz men, with the procession of musicians playing dirge on the way to the service and joyous music later on the way to the cemetery.

The new apartment, with the walls painted a crimson-maroon and with Mexican chairs and fur pillows from the trip to Mexico, hosted parties that emerged semi-spontaneously when before a big concert, Owen would buy a couple of cases of beer, and if the vibe was good after the concert, he would suggest that everyone come over to pick and sing. One night he and Jane found Bobby Neuwirth flat on the kitchen floor, having drunk not the beer but all of the two bottles of Châteauneuf du Pape that Jane’s parents had given her for her birthday. Jim Kweskin also remembered great moments in that room, with Marilyn [Kweskin] and Geoff Muldaur, “smoking a joint and listening to Owen's amazing record collection.” Friends from out of town stayed in that room, including Dick and Mimi Fariña, who made a small festival of the simple act of going down to Haymarket to buy peaches and blueberries.

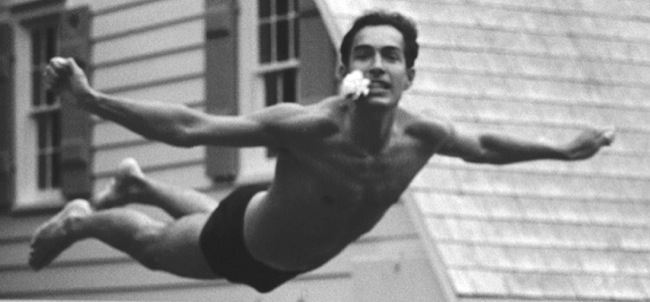

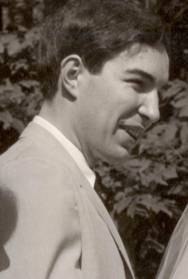

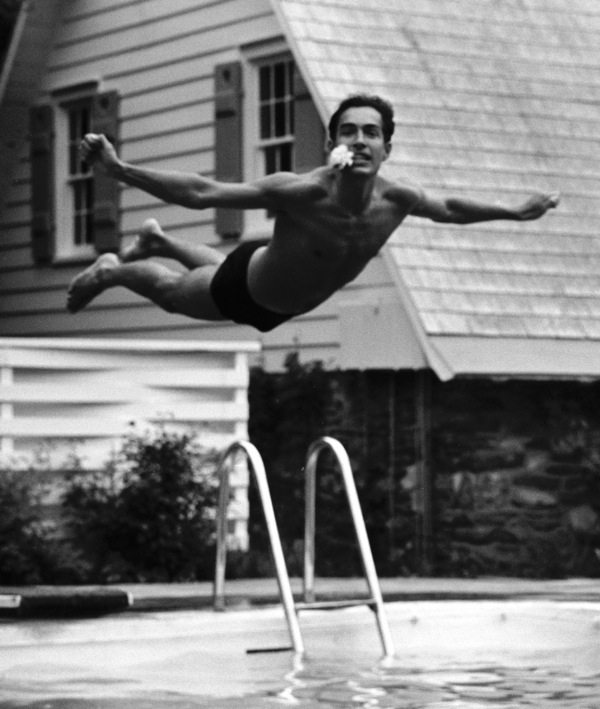

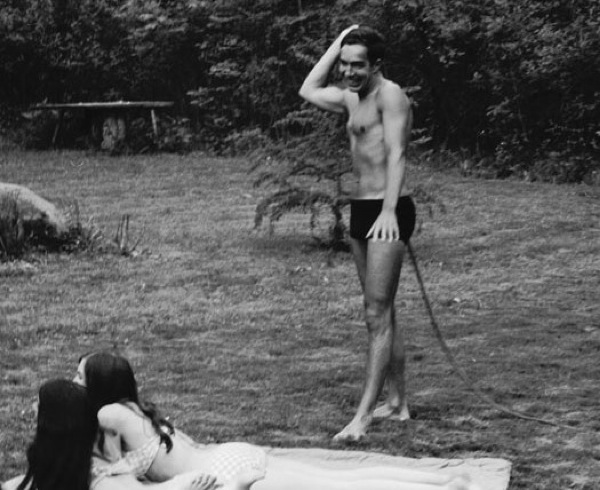

Owen and Dick got along well – the picture of Owen diving into the pool with a rose in his teeth comes from May 21 or 22, 1965, when Dick and Mimi were staying in Woodstock at Albert Grossman’s house. Here below is that photograph with more context. The next photograph, taken the same day, shows Owen laughingly pretending to attack Debbie Green and Mimi with Dylan’s bullwhip. Both are by photographer John Cooke, also of the Charles River Valley Boys.

In Cambridge, Owen had built a bookcase on the wall of the apartment to hold the inventory from the distributorship, “Riverboat Records,” that he had inherited from Geoff’s old friend Joe Boyd. The little company took 3% for distributing Arhoolie, Folkways, and other small blues and folk labels to the Harvard Coop, Briggs and Briggs, and other record stores in the Square. As part of the business, Owen kept one copy of each of the records that he liked, giving him a great collection of old blues and bluegrass. That distributorship later went to Ralph Dopmeyer and then evolved into part of Rounder Records.

In graduate school, Owen finished all his coursework, specializing in foreign policy. He planned to write a dissertation on Dean Acheson. His mission outside of class was the Americans for the Reappraisal of Far Eastern Policy, an early group critical of the war in Vietnam, led by John Fairbanks at Harvard and William Sloane Coffin at Yale. In that group he worked closely with Ric Pfeffer, the scholar and activist who died in 2002.

Jane remembers how Owen opened up worlds to her, including graduate school itself. Being born in 1939 and not to a later generation, she would not have attended graduate school had he not urged her to. Because of him she knew the excitement of the Club 47. When she failed her general examinations in the History Department at Harvard, he never thought twice about supporting her for a year, on his small Harvard Teaching Fellow’s salary, while she tried to figure out what to do next.

The sixties were the age of free love, and Owen threw himself into that the way he threw himself into everything else. He and Jane struggled with the repercussions, and in 1967 Owen asked Jane for a divorce. She moved out to live with Hildegarde Fuss (now Duane) in the apartment Jim and Marilyn Kweskin had just left at 131 Huron Avenue (photos and description of 131 in Mel Lyman’s Mirror at the End of the Road). Owen and Jane were legally divorced on June 17, 1968.

Jim and Marilyn had left their apartment to join the Lyman Family on Fort Hill. Much has been written on the Family, which continues to flourish, with compounds not only around Fort Hill in Boston but also in LA, on the Vineyard, at the farm in Kansas, and in Baja California. Shortly after the divorce, Owen decided to leave Harvard to join the Family on the Hill, and the experience changed his life. It was not just the acid he took with Mel but also the spiritual purpose on the Hill that made him turn his driving force toward accomplishing its missions. Mel Lyman, whom some considered a kind of god, was an intense and intensely authentic person, who could make everything else feel trivial. His music, and the music he inspired, could be intensely spiritual, as when he played “Rock of Ages” on his harmonica over and over for ten minutes in the dark at the end of the Newport Folk Music concert in the summer of 1965, while the crowd, many upset at Bob Dylan’s taking up electric guitar for the first time, listened, absorbed the calm and intensity of his wailing music, and slowly dispersed. The art in the houses the Hill renovated around the beautiful and desolate Fort Hill monument in the middle of one of the Black sections of Roxbury was also spiritual and deeply moving, as in Eben Given’s Daumier-like sketches in the Hill’s magazine, the Avatar. Owen was attracted by the depth of community on the Hill and by its mission to change the world.

On June 6, 1968, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. The Hill had looked to Kennedy for political leadership and the community was devastated. Some filmmakers on the Hill made a movie of the outpouring of grief, which they showed in a theater in Boston one night, with one long scene focusing on a close-up of Owen’s face in a paroxysm of sadness and despair. Throughout his life Owen kept a framed photograph of Robert F. Kennedy in a prominent place in his living room wherever he lived.

In 1978 Owen contributed these paragraphs to Eric von Schmidt’s and Jim Rooney’s book, Baby Let Me Follow You Down: The Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years:

The country followed Dylan off into rock music and others followed Mel off into Fort Hill in the end of ’66. I went in ’68. In ’68 I was still in my apartment in Harvard Square, but it was absolutely dead. I knew that if I stayed there one more year I was going to die myself. Martin Luther King getting killed and Bobby Kennedy getting killed was like the end of it. People came from all over the country in response to Mel’s message. There were ten people from Michigan who read an Avatar, took a train, wound up on Fort Hill, and are still there. I was a P.D. candidate in government and I was reading everyone in the world, and no one was making as much sense as he was. It was very clear to me. The spirit had gone there. He’s the kind of person who forces you to make a choice. If you are looking for what he is doing, and you see that he is really doing it, you either join, or you find a lot of reasons why not to join.

What I learned from Mel was that that whole revival of folk music and what happened around it was a gift from God and that, once having received it, you then had to work hard to do something with it. I was just a student at Harvard. The whole thing was a gift for me. It gave me all this music and all these people and all this life. Then, when it went away and I was still sitting there in my apartment, I realized that what he had been telling me for five years was true and that I had to go out and do something. I had being going to work for Bobby Kennedy. Now, where was I going to do it? With Melvin and what he was doing. That was it for me, anyway. It was time to get together with other people who wanted to have personal relationships and build and to have the faith that if we build honestly enough and long enough that we would at least create a life together. Everyone of us has had opportunities to do other things and yet everybody has stayed in the community, brought together by the music – which still binds us together. Music – folk music especially – is the binding force.

In the ensuing years, Owen stayed with the Lyman Family, moving to LA and then to the farm in Kansas.

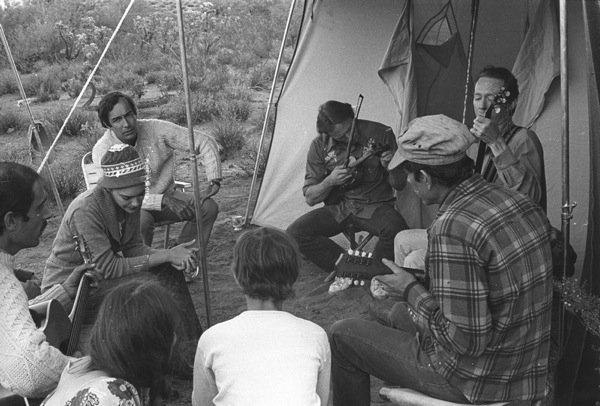

George Peper has contributed six of his photographs to this memoir. The first three are of Owen in New York in the 1970s, the next of Owen about to swim on a beach in the Vineyard, and the last two of a campfire, probably one evening on the Caravan.

Around the campfire, clockwise, beginning with Jim Kweskin (with guitar) bottom left, then Gale Lyman, Owen, Richie Guerin (with fiddle), Mel Lyman (with banjo) and David Gude (with mandolin).

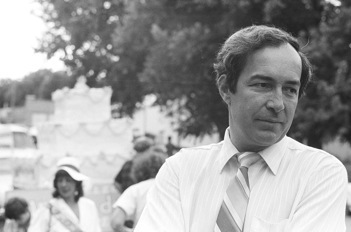

The Candidate Talks To The People

How Could You Not Vote For This Man?

Paul Jones for Owen de Long

Schmoozing With the Locals

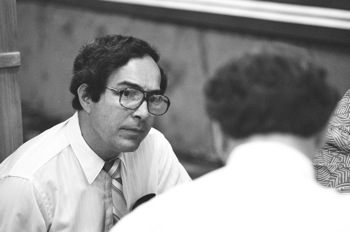

A Concerned and Thoughtful Candidate

A Good Listener

The Candidate in the Parade

The Campaign Trail

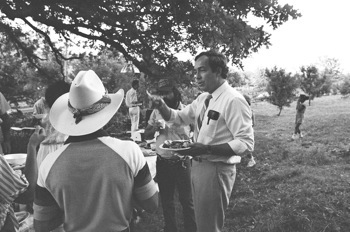

At The Campaign Picnic

Campaign Picnic

The Speaker

Giving His Speech

Practicing His Speech

Checking It Twice

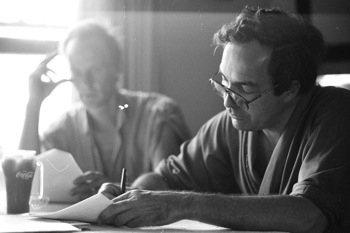

Writing His Speech

The 1985 campaign for the Democratic primary in the Kansas State Legislature tapped into Owen’s intensity, his intellectual and emotional commitments, and his concern for others. Jim Kweskin has chosen fifteen photographs from that campaign, taken by Kurt Franck, that are reproduced below with Jim’s captions.

When I was only about 23 years old, I lost a very dear friend of mine to a violent death. Nobody I loved had ever died before, and I was devastated and paralyzed with grief. Owen, who had been only an acquaintance and who was a good deal older than I was, recognized the depth of my despair and decided that he was going to take care of me. And when Owen decided to do anything, he was an irresistible force. He swept into my life in the same dauntless and ardent way that he did everything. I will always be grateful to him for that time. He saved my life and enabled me to go on.

When I think of him I think of those qualities. He was always brimming with some sort of idea or emotion or purpose. His fervor was boundless, for better or for worse! It could be a complex philosophical concept, a political cause, or just a great bottle of wine. Or beautiful first editions of books. God, he loved books!! We all have books inscribed by Owen. And he loved cataloguing things, endlessly. I can still hear the way his voice would rise when he was excited about something, or the unabashed laughter that came out of him when something struck his sense of humor, which was often. He loved being with people, and he appreciated them. Owen was a big and generous man, in everything he did.

Nell Foote also remembers Owen from this period:

Owen had an amazing mind. He carried a presence, a global understanding, and a dignity which was natural to him. Mel loved him, and deeply appreciated his succinct way of analyzing history. Owen was a born teacher.

I worked for him as a sign painter in Kansas when he was running for office, and I saw how much the local people were impressed with him. Even when his ideas were too broad for them, they genuinely liked him. He was an extremely likable man.

He taught history to a great many of our kids in home school. Sometimes he talked above their heads, but they shared his excitement, and they learned a lot from him. And he could make them laugh, while they were learning. Owen loved to laugh.

But when someone was hurting and needed help, Owen knew how to listen. He could be very empathetic, and he was a kind man.

I was born three months after him in 1939, and I will miss him.

Eben Given remembers:

Owen and I were close friends during his years in our Fort Hill family. We shared a passion for Politics and History, and could talk for hours together about them (often clearing the room of everyone else). I learned a lot from him and we had some fine arguments.

I was living on our Farm with Owen in 1985 when he decided to run for the Kansas State Legislature, and I became very involved in the campaign. It was quite a wild ride. Our district at that time had long been represented by a Republican named Lloyd Polson, who was pretty much in the pocket of big agribusiness. We were all deeply concerned about the damage being done to the environment and the farmlands by the rise of agribusiness and chemical farming, and Polson was an arch-villain in that regard. During the campaign, Owen always referred to him as “Lloyd Poison.” The name stuck.

The first step in the campaign for representative was a Democratic primary for the right to run against Rep. “Poison.” Owen’s opponent was a farmer from the next county named Bruce Larkin. He was a good man and strongly supportive of family farms and the environment. Throughout the primary campaign, Bruce and Owen focused their attacks on Polson, and had nothing bad to say about each other. They decided to have a series of debates through the campaign summer, going from town to town.

All of us, especially our kids, had a great time joining in the campaign events. We made signs and printed out literature, we decorated our old farm truck in red, white and blue for parades in every farm town in the district. The kids would ride on the truck, excited to be part of the fanfare. Owen would walk along beside waving and smiling. Larkin would be marching too, though he didn’t have nearly as many colorful signs and gleeful children.

Campaigning in Kansas is very local: it is based on meeting the voters and not on big money and TV ads. Owen probably shook hands with almost every voter in the district and had long conversations with many. Of course, a lot of voters in Marshall County, Kansas didn’t know what to make of this fellow from the “hippie commune”, especially since he sure didn’t seem like any kind of “hippie” they had imagined. He was smart and well-dressed and impassioned about their difficulties as small farmers.

It was an exciting campaign, and Owen hoped that this was the beginning of a political career that would lead on to great heights. Unfortunately he lost to Bruce Larkin in what was a surprisingly close primary election. Kansans understood Larkin, he was one of them. They were clearly impressed by Owen, but he was not quite “rural Kansas”.

But the end result was that Larkin went on to resoundingly defeat Lloyd Poison, in a district that had always been safely Republican. Larkin held onto the seat for 20 years, and was an excellent representative, fighting for the small farmer and for the environment. His victory was really a result of the inspiring campaign that Owen waged.

Randy Foote remembers:

From the early 1970’s until Owen decided to leave the community twenty years later, he was among my closest friends. We worked together on a number of environmental battles in the Eighties, most notably a successful campaign to save the Atlantic striped bass, which was then in danger of being overfished to extinction. Owen, like myself and many others in our extended family, had come to love recreational fishing for stripers on Martha’s Vineyard. With his political acumen, and meticulous attention to detail, Owen proved a key ally as we set out to convince sports fishermen across the Eastern seaboard to join our fight and also get the media to cover it.

In my memoir, Striper Wars, published in 2005, I wrote of our initial foray toward getting tougher regulations in Massachusetts: “Another friend, Owen de Long, the maitre d’ at a fancy Boston restaurant, raised the striper subject after finding a table for Boston Mayor Kevin White. The mayor agreed to sign a letter if Owen would write it for him, which he did.” Eventually the two of us formed a non-profit Striped Bass Emergency Council, while Owen and I testified before the U.S. Congress and appeared on numerous TV news shows. He was ready to do whatever it took. Eventually, even if reluctantly, so were all the state officials along the fish’s migratory path.

In Kansas, Owen was involved in a successful effort to prevent a nuclear waste dump from being built not far from the farm where he lived. He first entered the political arena there, running for the State Legislature in 1986, and I still remember the horse-drawn parade down the main street of Marysville on his behalf.

In U and I Magazine, published in the mid-eighties, Owen penned an impassioned call for a new political party. “Let’s start one called the BLUE PARTY, to parallel the Green Party in West Germany that’s starting to take such a hold. It’s blue like the sky when it’s clean, blue like the water when it’s clear, and blue like the shimmering jewel of the planet when seen from outer space. There’s plenty about this country and about this world right now to give everyone the blues. So let’s have a political party for everyone who has the blues, and wants the air and the water and the life to return to its natural vibrancy in the former land of the red, white and blue.”

His piece was headlined: “Every day I wake up wanting to start a new country.” Owen, like a lot of us, never achieved his dream of helping that come to pass. But it certainly wasn’t for lack of trying.

Dick Russell remembers from that time:

At night around the campfire, left to right, David Gude (with mandolin), Jim Kweskin (with guitar), Mel Lyman (with banjo), Owen, and Gale Lyman.

Owen drove the Pontiac GTO which was up in front. We called it ‘The Point Car.’ A perfect job for an Aries, leading the way. As we traveled, we camped out, sleeping in tents. All us guys slept in our sleeping bags wearing either jeans or in our underwear. Owen slept in smoothly ironed pajamas. I don't know how he did that. Everything I had was wrinkled.

Jim Kweskin remembers members of the family driving across the country in a "Caravan" of vehicles:

Owen was driving and George was co-pilot. We had all been driving in extremely hot weather for a day and a half, all thoroughly exhausted. We had pulled onto the side of the road. I believe one of the cars was having trouble and we were stuck in the heat for a few hours. We were all bleary eyed and grungy and all we wanted was to get some shut-eye. Everyone took the opportunity lay down and get a little rest. Everyone, that is, except Owen. At one point George looked up and saw Owen sitting in front of the car mirror shaving, combing his hair, splashing on cologne, trimming his nose hairs, and generally primping himself to perfection. And damn if he didn't look sharp. He could have been on the cover of GQ Magazine. He was wide awake and ready to go. Then we finally got back on the road, and lo and behold, about fifteen minutes down the road, Owen nodded out and fell asleep at the wheel and drove right into a corn field.... Got to love him. It's a funny story now. Luckily no one was hurt.

George Peper, Jim remembers, tells of another time on "The Caravan" when he and Owen were driving in the point car:

For instance, we had a great many books, some of them valuable. They were in a chaotic mess, completely out of order. Owen organized and arranged them to perfection. Even back in the day, his record collection was in perfect order. Which was great. We'd listen to a cut and someone would say, "Let's hear 'Gee Baby Ain't I Good To You' by McKinney's Cotton Pickers." Owen knew exactly where it was. And then while we were listening to that song, he'd put the last record back in its place so it could be found the next time it was requested. If you needed something organized you could always count on Owen to do it, better than you could do it yourself. I remember visiting someone's home and discovering, to our dismay, that while we were hanging out in the living room, Owen was in their kitchen re-arranging everything in their refrigerator. When they discovered it, the people were pissed. He just couldn't keep himself from organizing everything he came in contact with. Sometimes that's a good thing and sometimes not. Let's just say that sometimes he could be obsessive.

Jim also valued Owen not only for the fun they had but also as “a great organizer”:

While in the Family, some of the time Owen worked as a waiter in high-end restaurants, but when in Kansas he also answered an ad for work in a community college teaching American politics. His intelligence, energy, and drive made him a hit in teaching, and his colleagues at the college told him he ought to get his Ph.D. and become a teacher fulltime. He applied and was accepted at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, where he worked with Phil Schrodt and Misty Gerner. While at the university, he saw a psychiatrist, who advised leaving the Family. Jane visited him in Lawrence in 1992, after he had left the group, was still at the university, and had begun to take an interest in Kansas politics.

Phil Schrodt remembers clearly one discussion he and Owen had about grading: “Due to his prior work at Harvard, the department had given Owen an independent section of the introduction to international relations course to teach, and after the first exam -- all essays -- he had graded some thirty exams not just once, but twice, because he wanted to make sure he had graded each only after seeing all of the others. I indicated that this probably wasn't a sustainable strategy, and one simply had to accept a certain amount of subjective slack in evaluation. I don't know whether this persuaded Owen or not; his approach certainly reflected an intense desire to do college teaching properly.”

Phil also remembers that Owen had a hard time fitting in at KU, partly because he was substantially older than most of the students, with a vastly different set of life experiences, and partly because “the KU graduate program had very limited financial resources, particularly compared with Harvard, and tended to focus on fitting round pegs into round holes, not exactly a strong point with Owen.”

Jim remembers too that “Owen had numerous political talks with Mel. Mel especially loved his mind. Owen was brilliant.” And Owen cared a lot for the music they made. He was at the recording sessions for the Jim Kweskin's America album, “where you can clearly hear his choir-like voice on ‘Old Black Joe.’ In Mel's captivating and fanciful liner notes for that album he refers to Owen as ‘Jim's Road Manager, O.D. Long.’ Well, he wasn't really, but it sounded good. He could have been.”

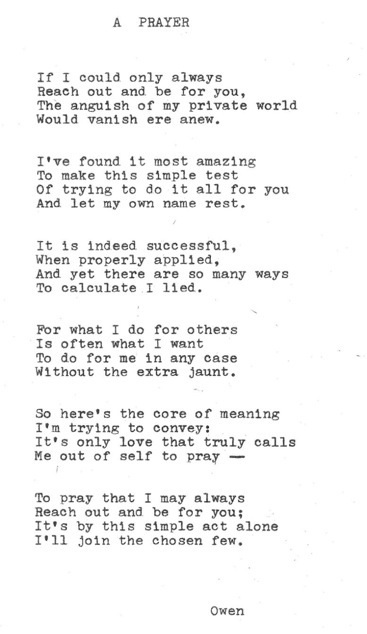

Sofie Lyman contributed to this memoir a poem she found that Owen had written “many years ago,” perhaps around this time, that shows him, in his words, trying to conquer the “anguish” of his “private world” through love:

My first memory of Owen was when I was about 11 years old in Boston. I had a fervent love for Somerset Maugham and he and I had a long conversation about the books. When Owen discovered my love of Maugham, he personally procured for me first editions of all of Maugham’s writings. These gifts were gems to me and I read each one cover to cover. This collection was my only personal possession that I kept with me from then until I was about 16, when the collection burned down in a fire.

Much later, Owen and I had apartments next to each other when I was a senior at the University of Kansas. It was a particularly dark time in my life and his too. His girlfriend had moved out and he and I would meet up each evening, either to eat dinner together or just do homework. He became my closest friend, confidant and advisor. We talked about everything from the environment to relationships. He was a huge comfort, like having my dad right next door. I will always remember him as a mentor, a friend, and a kind of father.

Deirdre Goldfarb, who grew up on the Hill and is still in the Family, writes:

Peter Gustafson, a classmate at KU, remembers Owen vividly as having “elevated my life into realms I would never have known in his absence.” He speaks of Owen’s “nobility,” his “rare level of intellectual, cultural, and spiritual breadth,” and his capacity for making one feel, in his presence, “that anything was possible.” His flaws were often the flip side of his virtues, because Owen had a “high opinion of himself,” as Peter remembers their walking around looking at the KU professors’ homes and Owen thinking he might someday join “the KU faculty himself as a professor.” Peter also remembers Owen’s “generosity, civic spirit, and love” for others. In Peter’s words, “he tempered vanity with humility.” Peter also sent for this memoir a page from Grant Lewi, Heaven Knows What (1939), a book on astrology that Owen had given him, and that Owen thought described his own character relatively well. “As a master astrologist,” Peter comments, “he was well aware of his flaws and strengths.”

the Republican-voting segment of the American electorate currently constitutes what I call an “enclave” of self-reinforcing, cognitive-data-excluding opinion-holders locked in a specific “state of mind.” This state of mind is so geographically as well as ideologically removed from the social and legal realities of those in the population centers of the two coasts and the Great Lakes region—most of whom tend to vote Democratic—that they have come to believe and defend the misinformed tenets of their paranoid world outlook like a typical populist conspiracy movement of the late nineteenth century in America.

Yet this accusation of removal from reality is not coincidental, since the Republican voters of today’s American “enclave” tend to espouse current policies based on unmodified fundamental values from two-hundred-plus years ago, values at the heart of our nation’s original and intentional separation from the rest of the world. While this patriotic association with our founding assumptions gives Republican beliefs a certain heart-felt electoral advantage over those who would seek to modify the Founders’ values in the light of present and future realities, current Democratic values, beliefs, and policies have their own anachronistic quality, being based for the most part on a world-view almost a hundred years old—from the Democrats’ era of greatest electoral success, the 1930s, the era of the Great Depression, FDR, and organized labor.

Owen left the university without finishing his doctorate in order to turn his forces of intelligence and drive to the political world in Kansas and to writing. For his 2006 Harvard reunion report, he summarized some of the themes of the book he was writing (which he was not able to finish). He had realized, he wrote, that:

[W]hat are the fundamental values and unique policies appropriate for the United States in the world of the twenty-first century, and who will emerge in the congressional elections of 2006 and the presidential election of 2008 to articulate them—and thereby decisively guide the American electorate away from values and policies now centuries old, as espoused so far by both major political parties? Surely these values must include a renewed global religious and cultural tolerance on our part, a recognition of worldwide interdependence and the need for further integration of our country into the family of nations, and an emerging awareness that China and India will eventually become the No. 1 and No. 2 economies on the planet, necessitating our submissive adaptation to a peaceful role as No. 3—without employing our nuclear “toys” in a childish and fruitless fit of role adjustment from having been the world’s hegemon for the past century.

He planned to end that work by asking:

I always thought I would wind up in Washington, DC, serving a progressive president of the United States at State, Defense, Treasury, Commerce, or the EPA. But then a four-fold tragedy rearranged our lives in the 1960s: the assassinations of JFK, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and RFK. The national soul was killed, the dream of global unity hatched from the camaraderie of the battlefields of World War II died, and suddenly our nation was pitched into forty years of deep distrust of the government created to provide and to protect our rule of law under the greatest written constitution in human history.

I instinctively retreated into an artistic community, to escape what were to me the most personal political and economic horrors of the 1970s and 1980s, and to attempt to establish a new society out of new relationships and old values, in contrast to the society I no longer recognized as my own. When I reentered the larger society in the 1990s, it was like trying to live on the moon. I had a few old friends here and there, but this new world was largely devoid of meaningful ties to me, because, after eleven years at Harvard in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, I had a twenty-year record of inherently internal accomplishments, deeds that were not recognized as the new coin of the realm. So I took adjunct teaching jobs, and food and beverage jobs, until I could build up a new corps of friendships, relationships, and meaningful ties with people in this larger society, which still felt so alien to me.

Having first come to the Midwest (Kansas) on a 1965 drive-by transcontinental trip, I came again in 1973—to help our classmate Jessie Benton start an organic farm for growing healthy crops and providing her children and her friends’ children with a cleaner environment than was possible on the two coasts, even in those days. Here they could retreat into nature, walk, plant, harvest, and generally recover. And I did too. I wound up staying into the 1980s. I augmented homeschooling of some of the extended family’s children with teaching at Kansas State and then at the University of Kansas, at which some of them matriculated. This college teaching occurred after I had made a 1986 electoral run at the intractable chairman of the Agriculture Committee of the Kansas House of Representatives, which helped remove him from his post. He was a pesticide salesman without a conscience, and would table in his key committee any proposed bill attempting to help save even the “home eighty” of farm families who had trustingly invested in big acres, big machines, and big debt in the late 1970s, soon to be faced with plummeting world grain prices from the unanticipated successes of the “Green Revolution” of pesticides in Asia and Latin America and all around the world.

But what really grabbed my attention just five years ago out here in Kansas was a massive and clandestine scheme—using taxpayer money at the federal, state, and local levels—to aid and abet the overwhelming desire of Walmart, and other big-box retailing corporations, to turn the Kansas City area into the North American transportation hub for the servicing of all their stores on this continent with their products made in China and in the rest of Asia.

This development had taken place, increasingly, at the expense of American manufacturing capacity and jobs, and of the health and security of this once sleepy and relatively clean and safe midwestern area of the nation. The scheme was nothing less than a two-pronged spear aimed at the heart of the Midwest. Both prongs eventually would be aimed at Kansas City, the first overland by rail from the west on the trains of the Burlington Northern and Sante Fe (BNSF) Railway, from ports on the American and Canadian Pacific coasts, to a giant “inland intermodal hub” to be built on the existing croplands of Gardner and Edgerton, Kansas. This transportation hub would feature diesel trains, diesel off- and on-loading cranes, diesel eighteen-wheelers, and diesel planes spewing diesel particulates into the air and into the waters of what was formerly farmland. Such activities had already proven that they would have a very deleterious effect, from their concentrated outcome for a decade at the other end of these trains’ runs, at first off-loading lines of relatively smaller ships, polluting as they waited for days at sea, and since 2006 offloading giant aircraft-carrier-size ships, stuffed ten football fields long and two fields wide each with Walmart’s cargo containers from China. This process had already led to the ruin of environmental and property values in vast areas around the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, with miles of verified cancer-causing plumes of carcinogenic diesel particulates filling the air—and innocent citizens’ lungs, young and old—in what had become, according to the Seventh Annual Report of the American Lung Association, a “dire” citywide health emergency.

This “hub” madness had just begun to be publicized in the Kansas City Star, on July 22, 2006, as I began to help Nancy Boyda, through her campaign-manager husband, turn the situation (in her second run for the Second Kansas US Congressional District seat) into essentially a one-press-conference, one-public- debate, one-newspaper-special-insert rout of her ten-year incumbent opponent. Calling all the mounting talk of an approaching “NAFTA supercorridor” a “myth of the blogosphere,” he was roundly booed for saying so at a noontime forum televised by all the local network stations and henceforth refused, for the ensuing two months of the campaign, ever again to appear in a public debate with her. In other words, one issue, and Jim Ryun suffered one huge and sudden loss of his seat. I continued to counsel Nancy daily by phone as her informal policy adviser during the two years she served in Washington, DC, as the US representative from the Kansas Second District, while the issue of the impending construction of one or more centralized transportation hubs in the area continued to grow.

Meanwhile, the “hundred-year dream” of the founder of the Kansas City Southern Railway had begun to be realized just across the Kansas-Missouri state line (see the June 16, 2006, cover story of Forbes magazine, entitled “The China-Kansas Express”), as the Port Authority of Kansas City, Missouri, prepared to sell a prized local asset to Center Point Realty Services Corporation of Chicago so it could begin to develop the second point of the Walmart delivery-of-goods spear. This was to be an “inland intermodal port hub” for the other major railroad servicing the area, at the southern Kansas City site of the former Richards-Gebaur Airport, the type of site Kansas City Southern had always coveted for that purpose. This second “hub”—in Missouri, but only a few miles east across the state line from the one proposed for BNSF in Edgerton, Kansas—was to have the same purpose and was thus to become a direct rival to it, except with a different back-end strategy, for a different railroad.

The key step in the dream of the KC Southern Railway’s founder was to establish special rail depots at ports on the Mexican Pacific, both to make use of the less expensive Mexican off-loading labor there and to use the existing KC Southern Railway rights-of-way through Mexico, through a little stretch of Texas, and then up through Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri to its own centralized transportation hub. This hub would be located at the very center—and hence at the most economically efficient distribution point—of the giant North American market for all of Walmart’s goods made in China, i.e., once again, at a point right in the middle of my new, and future superpolluted, home in southern Kansas City!

Spurred by these developments, I have taken this issue up as my principal cause in these later years of my life here in the Midwest. This is a land that, before all this massive globalization of production and distribution started to hit us here—and hit us suddenly, and right under our formerly peaceful noses—I had begun to regard as a much healthier and safer land of repose and rest in which to spend the rest of my life. I would rather live here than on either of the now especially polluted and hectic coasts, both of which I had experienced as all too threatening to life even in my youth and beyond. Now I am devoting part of every day to writing a book, several articles, letters to the editor, and new legislative testimony to try to slow, even to stop, this behemoth that has so rudely invaded our formerly tranquil garden of nature.

Ironically, local citizens’ efforts are actually being augmented by the strong legal help of the New York–based Natural Resources Defense Council, a major partner of whom is Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., completing something of an adult-lifetime circle for me personally. On March 17, 2008, I testified for an entire afternoon before two different committees of the Kansas Legislature on this subject, but to no avail. In May of 2010 a majority of the legislature voted in the dead of night, out of scarce taxpayer money, on the last day of this year’s session, in favor of—and got the governor’s required signature on—a special $35 million “corporate subsidy,” or incentivized gift, to BNSF’s new owner, multibillionaire Warren Buffett and his Berkshire Hathaway holding company—if he and they would just restart their “intermodal hub” project in Edgerton, Kansas (put on hold for over a year because of the 2008 recession) by the end of 2010.

So there is much work to be done around here these days, since it has once again come down to what D. H. Lawrence was writing so eloquently about in England exactly one hundred years ago. It’s all about the modern human predicament of which will eventually prevail: lives lived for the good of people, or lives squandered on the accumulation of wealth and its nefarious handmaidens, our more and more destructive machines.

Owen’s work in Kansas included deep involvement in Nancy Boyda’s two campaigns for Congress, working with her husband, Steve Boyda. In 2011, he wrote a long essay for his 50th Harvard reunion on the trajectory of his life and his urgent concerns for the environment:

I met Owen nearly 30 years ago. From day one, he expressed his passion for national politics and the unfolding events of the day. Owen stood a head above most because he had a grasp of history behind national and foreign developments. His run for the Kansas Senate in the 1980's provided a colorful opportunity for him to introduce himself to Kansas voters. He said, "I offer the voters a new and different kind of candidate, a contrast, a choice. I am not a conservative. I am unabashedly a liberal. I am not a native from Kansas; I come from Boston. I am an easterner, not a mid-westerner. Nor can I claim to have attended either K-State or Kansas University, Harvard was my home. I am not a farmer; I am a political scientist with an emphasis in Chinese relations. Do you need any greater contrast between my opponent and me?"

In 2006 Owen and I together authored the campaign insert newspapers for the Nancy Boyda campaign for US Congress. Nearly a million insert copies (14 pages each) were distributed to Kansas voters, who then turned Tim Ryun out of Congress in favor of Nancy Boyda. During Nancy's term, Owen wrote weekly position papers on the major developments of the day. Often these became daily reports that the Congresswoman could review early in the morning. During that time Owen and I also conducted issue seminars around the state, addressing current political issues. From Garden City to Kansas City, from Pittsburg to Topeka, Democrats had the opportunity to have in-depth discussion of issues of concern.

Owen's dream was to publish a book on the major political developments of our lifetimes. For him, the crucial issues were the loss of US dominance in foreign affairs, the pre-emptive strike as a departure from the Eisenhower doctrine, and the growing role of corporate financing and the influence of the military industrial complex, with the concurrent diminution of civil liberties. His outline planned an historical discussion to underpin these issues. Try as he might, the flood of events at the end of Bush and beginning of the Obama Administration, together with his health challenges and the traumatic passing of his partner, Susan, stymied his attempts to finish the book.

Steve Boyda remembers this time:

Steve contributed the following photographs:

Owen had kept in touch with Jane. One evening in the spring of 2010, he called her in despair. His partner of several years, Susan Stuckey, had just been shot by the police. She had had emotional problems and Owen had protected her. He thought of her, Steve Boyda said, as a beautiful little bird in a cage that he hoped to set free. Over the years, however, her paranoia grew and she alienated all of her friends. Finally even Owen had to move out. That morning she had called him and told him of her fears that attackers were invading her apartment. She had had interactions with the police and they were coming to her house. Owen told her to do nothing more and that he would be right over. When he got there, the police said that when they had come to the door they had found it blockaded. They had battered it down, and after they entered, Susan had attacked them with a baseball bat. They shot to kill, and they killed Susan.

Owen was devastated by this loss. He sank into a depression, was eventually taken to a hospital, given medication and released, but he did not improve, and began not answering the calls of his old friends Peter Gustafson, Steve Boyda, Jane, and his sister Suzanne. Steve Boyda visited and urged Owen to move in with him, in a small room with a bath that Owen had once lived in. Steve also said that he cooked for his mother and could cook for Owen too. Owen did not take up the offer. Steve worried because Owen seemed not to be eating and, when Steve visited, Owen came to the door in his pajamas and bathrobe. It seemed later as if Owen had made a decision to stop. On September 11, 2013, the janitor of the building, the Heartland, found Owen’s body. He had been dead for more than a week. It is possible that he starved to death – a form of death that is said not to be painful, but to result in less and less energy and finally in sleep.

His friend Peter Gustafson has these thoughts:

Owen’s desire for a loving relationship with a woman was what mattered most to him. In spite of a glorious abundance of talents and aspirations, this is what he most desired. Other people, lacking love, learn to persist and even thrive on other sources of meaning and sustenance. Owen was not one to compromise. He was not one to live at "half mast." Life was all or nothing for him. Lacking love, he felt that he had nothing to live for.

Owen and Susan met in the course of the 2006 campaign, where they became close, watching each other's back, so to speak. They shared a love of music and environmental concerns as well as a companionship and love that carried them through challenges that others would not have been able to weather. But fate was not to be kind to them. After Susan was killed, Owen was never the same. Her loss and his reaction gave definition to the depth of his love for her.

Owen is now at peace, a peace he so badly wanted for the nation and, more importantly, on a personal basis. His friends here will miss Owen's Aries passionate nature. We will miss a friend who would challenge you to think. His students from several colleges have lost one of the most vibrant instructors they have had.

His friend Steve Boyda adds:

Owen is survived by his sister, Suzanne de Clercq, of Naples Florida, by her two children, Trevor Owen de Clercq and Oliver Winfield de Clercq, and by his great-niece Hazel Jane de Clercq. Trevor Owen graduated from Cornell in music, got his MA from NYU and his PhD from Eastman. He now teaches music theory and music technology in Middle Tennessee State University outside of Nashville. In September 2013, just as Owen was dying, Trevor Owen and Sarah de Clercq became the parents of Hazel Jane. Hazel will remember her great-uncle because her father bears his name. Perhaps she will one day read this memoir. Oliver Winfield de Clercq graduated from BU in music and went on to study the French horn at Juilliard, but before even finishing his degree won an audition for the Vancouver Symphony, where he has has been principal horn for 13 years. Oliver has a six-year old son named Ethan. Suzanne reports that she has suffered from depression but found relief after the shock treatments that also helped her mother. Recovered, she now teaches piano in Naples. The family has thus carried on their grandparents’ musical tradition, to which Owen in his way also contributed.

Owen had a full life. May he rest in peace.

This memoir was written by Jane Mansbridge, with help from many of Owen’s friends. The Cambridge years are described well in Eric von Schmidt and Jim Rooney, Baby, Let Me Follow You Down: The Story of the Cambridge Folk Years (N.Y.: Anchor Books/Doubleday 1979) and in Mildred Rahn, “Club 47: An Historical Ethnography of a Folk-revival Venue in North America, 1958-1968,” M.A. thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1994. See also New England Music Archives, now ‘Folk New England’ (http://newenglandfolkmusic.org/). The photograph of Owen diving, taken by photographer John Cooke, and reproduced in Schmidt and Rooney, and that of Owen with Bob Dylan’s bullwhip are used by permission (Photo © John Byrne Cooke). The two Club 47 calendars are also taken from Baby, Let Me Follow You Down and are used by permission.

Geoff confirms Maria’s account, adding, “He really did save Maria's life and maybe mine. If he hadn't been there to push her into shore, I might have stuck around too long and ‘bought the chops’ (von Schmidt term) myself. It was quite a heroic act.”